From “Agents” to Autonomy: A Practical Framework for Agentic AI (Levels 1–5)

Business leaders today are inundated with claims that artificial general intelligence (AGI) – a human-level, autonomous AI – is just around the corner. Headlines trumpet looming “super-agents” that might soon replace knowledge workers, stoking both excitement and anxiety

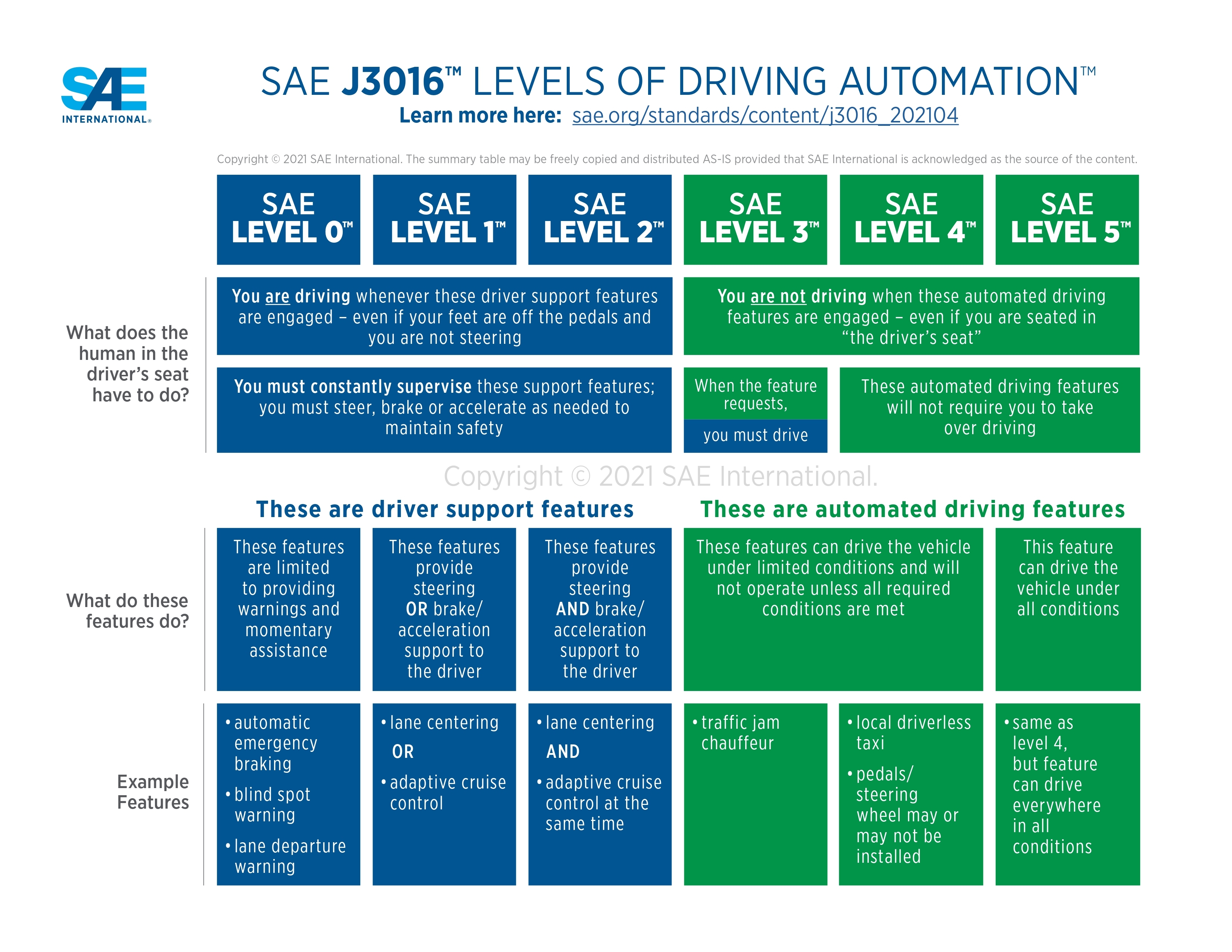

Agentic AI has become the enterprise buzzword of 2025, referring to AI systems that can act with some degree of autonomy to achieve goals, emphasis on ‘degree of autonomy’. The Society of Automotive Engineers addressed a similar challenge with the advent of self-driving cars, defining expected functionality and the necessary human oversight for safe and effective operation.

Just as autonomous vehicles use SAE Levels 0–5, AI systems need a shared vocabulary for autonomy. This post turns a live, complicated discussion into a clear, practical guide you can use to plan, scope, and safely deploy agentic systems inside real organizations.

Defining Autonomy

It’s worth noting that the functionality gains from one level to the next in the case of self-driving cars are non-linear. In fact, it’s been nearly a decade since Elon first promised that fully self-driving cars are around the corner, yet Teslas (no matter how great they operate *most of the time*) still require humans to be able to seize control at any moment. And yes, we have Waymo operating in limited environments

The problems to solve (and the cost to solve them) jump exponentially at each level, and we posit that, just like fully autonomous self-driving cars at level five that can operate anywhere, we are a far way off from seeing level five agentic AI operating at the “PhD” level as Sam Altman describes it. And the authors both firmly believe that LLMs are not the architecture to get us to level five, but that is a discussion for a separate post.

The Five Levels of Agentic AI

The challenge with the current narrative around Agentic AI is that it paints all autonomy with the same brush, with many claims of models “quickly improving” to “superhuman levels.” These arguments miss the point. Autonomy isn’t a binary “yes” or “no.” It occurs along a continuum of generalization, human-AI collaboration, and oversight.

To make the phrase “Agentic AI” more productive, we propose the taxonomy below, inspired by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s definitions of self-driving.

**Note: The authors do not believe that this level of autonomy is reachable in the short term.

Level 1 — Deterministic Task Bot

What it does: Executes a narrow, predefined action with minimal reasoning.

Example: Password reset workflow; triaging tickets; filing a form; scheduling a meeting with fixed templates.

Human oversight: Required for edge cases; output is easy to verify.

Tooling/permissions: Single system or API; no spending authority.

Where it shines: High-volume, low-variance tasks you could have automated even pre-GenAI—now easier to build and maintain.

Level 2 — Preparatory Agent

What it does: Drafts, proposes, or partially executes multi-step tasks; always requires review.

Example: Draft contract redlines; compile weekly business summary; propose a JIRA triage plan.

Human oversight: Mandatory review/approval before anything hits production or customers. Treat like a new hire you’re training.

Tooling/permissions: Multiple tools (email, docs, trackers) in read/limited write; no autonomous spending.

Where it shines: Knowledge work with templates, checklists, and strong reviewer SLAs.

Level 3 — Narrow Operator

What it does: Handles routine workflows end-to-end; escalates uncertain cases.

Example: Close-out support tickets, run weekly reporting, push low-risk config changes, prepare e-commerce listings.

Human oversight: Spot checks; “trust, but verify.” Humans remain on the hook for final accountability.

Tooling/permissions: Broader tool access; constrained writes; may trigger pre-approved micro-actions (e.g., issue credits up to $X).

Where it shines: Stable processes with known exceptions and good audit trails.

Level 4 — Semi-Autonomous Specialist

What it does: Operates correctly the vast majority of the time (think ~98%), including planning, tool use, and recovery from common failures.

Example: Price monitoring and reordering with budgets; lead-to-opportunity routing; L2/L3 IT ops playbooks with rollback; travel booking within strict constraints.

Human oversight: Humans in the loop; approvals only for out-of-policy events, anomalies, or high-impact decisions.

Tooling/permissions: Multi-tool orchestration; bounded time/budget authority; strong guardrails (rate limits, RBAC, circuit breakers).

Where it shines: Medium-risk domains where the cost of delay > cost of occasional correction, and where governance is robust.

Level 5 — Autonomous Problem Solver

What it does: Pursues open-ended goals, decomposes novel problems, and generates new knowledge or strategies (the “PhD-level” analogy).

Example: New algorithmic ideas; novel drug hypotheses; independent market entry strategies.

Human oversight: Policy-level supervision and after-action audits—not step-by-step review.

Tooling/permissions: Broad read/write with explicit scoping; significant resources; programmatic ethics/compliance gates.

Reality check: Technically exciting, but unnecessary—and unsafe—for most enterprise workflows today. Treat as research, not production.

One Size of Autonomy Does Not Fit All

Our taxonomy is primarily organized around user control and tool scope as these are the most visible features to end users. That said, we recognize that other dimensions may be helpful for classifying the autonomy of agents at different levels.

- Task complexity: The amount of human time typically required to perform a task is a reasonable proxy for complexity. One-shot actions (e.g., sending an email) are more straightforward than complex, multi-step tasks (e.g., researching various options before purchasing).

- ROI potential: A very direct measure of agents is the potential for economic impact, cost savings, or revenue generation. OpenAI recently introduced a benchmark, GDPVal, that evaluates various AI models on real-world economic impacts.

- Domain risk & consequence: Legal, healthcare, finance, and safety-critical ops require tighter guardrails than marketing or internal ops. Such industries will have different tolerance levels for the adoption of autonomous agents. Auditability and explainability may be required as an additional layer of implementation here.

- Multi-modality: The majority of agents in production today work well only with plain-text documents, with strict limitations for reading images, tables, charts, audio, and video. As models and other engineering tools are implemented, agents will be able to consume more data sources to make more informed decisions.

Making Agentic AI More Productive with a Taxonomy

A shared taxonomy gives us a cleaner way to talk about autonomy. Right now, everything from a scripted workflow to a multi-tool planner gets labeled an “agent,” which blurs important differences in oversight, permissions, and expected behavior.

Most organizations will harvest outsized gains from well-governed Level 2–4 systems long before Level 5 is necessary. If you take one next step this quarter, pilot a single Level-2 workflow, define necessary human oversight and success metrics, and iterate toward bounded autonomy. The result isn’t just faster execution; it’s trustworthy automation that your teams understand, your auditors can verify, and your customers actually benefit from, at a lower total cost of ownership.

We encourage you to treat this framework for agentic AI as a living document. Our goal is a shared language that makes it easier to argue less about what an “agent” is and focus more on what type of autonomy is needed. If you are mapping your own workflows to these levels, or finding edge cases that do not fit, we would like to hear from you.

As scientific and engineering breakthroughs accelerate, we expect the average level of these agents to rise alongside them. Regardless of the pace of change, it is clear to us that setting clear user expectations is what will drive successful adoption.

About the Authors

Cal Al-Dhubaib is a data scientist, entrepreneur, and innovator in responsible artificial intelligence, specializing in high-risk sectors such as healthcare, energy, and defense. He is the Head of AI and Data Science at Further. Cal frequently speaks on topics including AI ethics, change management, data literacy, and the unique challenges of implementing AI solutions in high-risk industries. His insights have been featured in numerous publications such as Forbes, Ohiox, the Marketing AI Institute, Open Data Science, and AI Business News. Cal has also received recognition among Crain’s Cleveland Notable Immigrant Leaders, Notable Entrepreneurs, and most recently, Notable Technology Executives.

Ivan Lee graduated with a Computer Science B.S. from Stanford University, then dropped out of his master’s degree to found his first mobile gaming company Loki Studios. After raising institutional funding and building a profitable game, Loki was acquired by Yahoo. Lee spent the next 10 years building AI products at Yahoo and Apple and discovered there was a gap in serving the rapid evolution of Natural Language Processing (NLP) technologies. He built Datasaur to focus on democratizing access to NLP and LLMs. Datasaur has raised $8m in venture funding from top-tier investors such as Initialized Capital, Greg Brockman (President, OpenAI) and Calvin French-Owen (CTO, Segment) and serves companies such as Google, Netflix, Qualtrics, Spotify, the FBI and more.

%20-%20Banner.png)